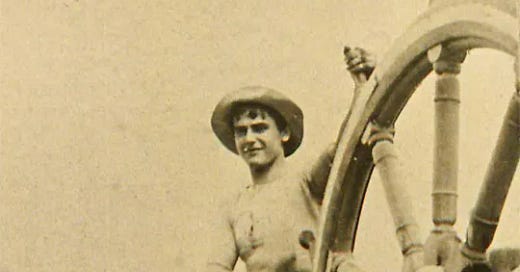

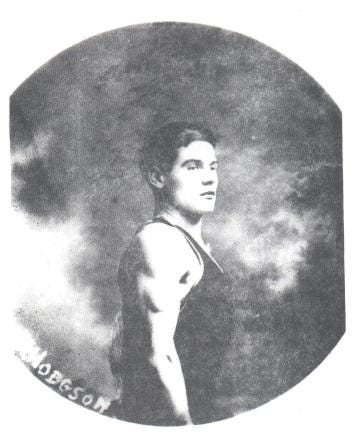

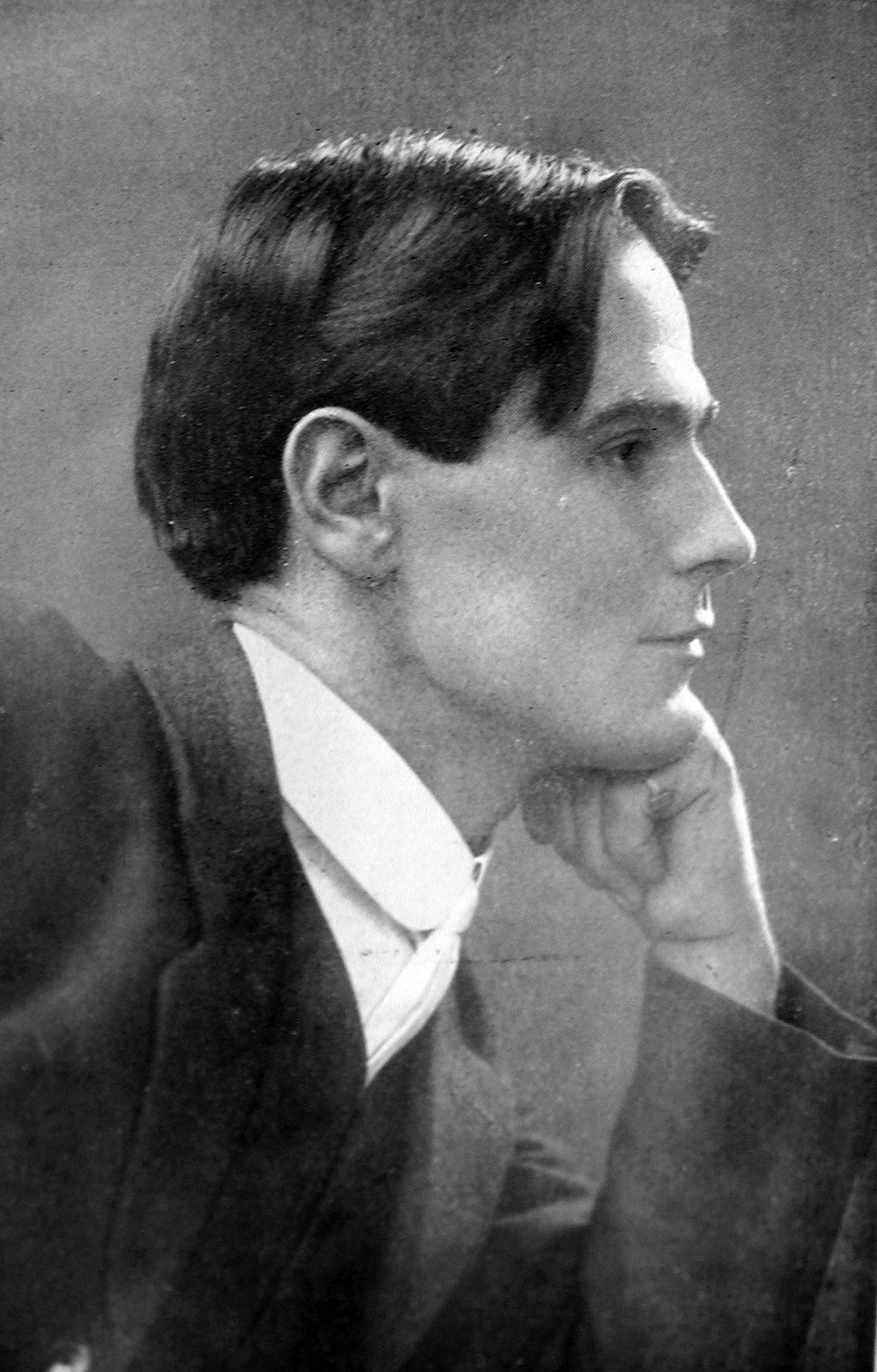

William Hope Hodgson (1877-1918) was apparently some sort of ideal man… Unusually brave both on a physical and spiritual level, uncommonly tenacious, bounding back from everything thrown at him, unapologetically romantic with a poetic heart, and seriously committed to personal hygiene. On top of that, very handsome and one of the strongest men in England at the time. What’s not to like?

He went to sea at age 14, where he was bullied by the adult seamen for his short stature and and cute face, which made him vow to become the strongest in any group henceforth. He began training vigorously, and successfully. As his fellow seamen came to experience, in Sam Moskowitz’ words:

When they moved in to pulverize him, they would learn too late that they had come to grips with easily one of the most powerful men, pound for pound, in all England.

Short but fierce, like Marvel’s Wolverine. In 1898 Hodgson received a medal for saving a fellow seaman’s life who had fallen overboard in shark-filled waters off New Zealand’s coast…

But the hero came in time to detest the sea, not least because of the then abominable hygienic conditions aboard a ship. He was a capable photographer, and apart from documenting spectacular natural phenomena at sea, he also documented the maggot-infested food… He hated mold, and fungus, and pigsties (pigs were also kept on ships), as testified by their reappearance in his horror stories.

So he returned to England in the year 1900 and went on to become what we would today call a fitness expert — making history by opening The School of Physical Culture in Blackburn to teach people how to take care of their bodies and build them up to maximum capacity.

When the legendary escape artist, Harry Houdini, during a European tour visited Blackburn, Hodgson was the one to shackle him — almost defeating the legend by applying his expert knowledge of anatomy when handcuffing him. Houdini did manage to escape after two hours, but was left with lifelong scars from the ordeal, and a grudge against Hodgson.

When it turned out after some time that, in spite of the school’s popularity, it did not make Hodgson enough money to live on, he decided to become a writer instead… My, how times have changed! Verily, people then were more interested in reading than in fitness… making the spinning of seamen’s yarns, and weird tales, and dystopic novels, a more lucrative way of earning one’s bread… Now, the opposite is certainly true.

Anyway, after a period of initial rejections, Hodgson became succesful as a pioneer of the genre of weird tales (both novels and short stories), alternating with horror and tales of the sea. He created one of the earliest occult detectives: Thomas Carnacki, the ghost finder. One of the entertaining aspects of a Carnacki story is that you never know at the outset whether the culprit will turn out to be an actual otherwordly entity or a hoax — or both!

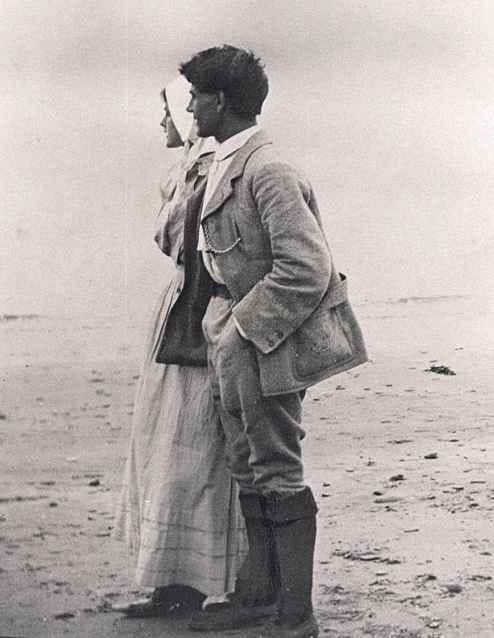

In this way, Hodgson could comfortably provide for his wife, his widowed mother, and sisters. The photo below is of Hope (as he was called by family and friends) with his favourite sister, Lissie, on Borth Beach.

He married rather late in life, at 35, but happily. (Allegedly, there was an earlier romance ending in heartbreak, but not much is known of that.) His wife Bessie, who was also 35 when they married, and is portrayed below, took care of his literary estate after his early death.

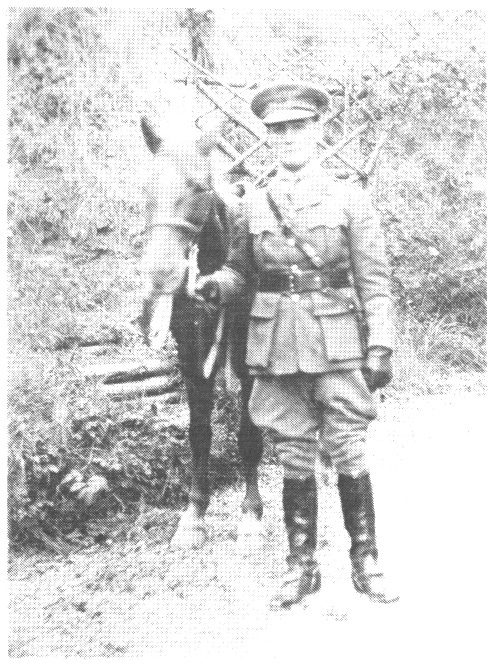

That he did not live longer was owed to the qualities I lauded above: His tenacity and unquenchable bravery. It was also caused by his acquired loathing of the sea. For when World War I broke out, and he volunteered, he blankly refused to serve in the Navy — which would have been far safer than being an a soldier on land, inevitably going over the top in suicidal conditions sooner or later.

Hodgson was given a second chance of survival when he was seriously wounded by being thrown from his horse. Among the injuries were a complicatedly broken jaw and a severe concussion. He was so smashed up that anyone else would have been invalidated out of the war for good. But he refused to accept this verdict, fiercely training himself back to health and then returning to the battlefield.

This time, he was given no further chances.

The way he died was entirely in character with the rest of his life. R. Alain Everts recounts his death as follows (quoted via Sam Gafford’s Hodgson site, read more here):

On the day of 10 April 1918, the Germans launched a big attack, and apparently this put Hodgson in hospital briefly. On the night of 16 April the Battery withdrew, and a Forward Observation Post was set up. The man who volunteered for the Forward Observing Office the next day—17 April—on Mont Kemmel, was none other than W. Hope Hodgson. (…) His Commanding Officer (…) on Thursday, 18 April (…) sent Hodgson with another N.C.O. on Forward Observation. On 19 April, Hope was heard from once and then there was silence from him for the remainder of the day. That day, 19 April, William Hope Hodgson was reported missing in action to his C.O. The following day, under continuous fire, the C.O. went to check himself to determine the fate of his F.O.O.’s. He eventually found a French officer who showed him a helmet with the name Lt. W. Hope Hodgson on it—and reported that a British Artillery Officer and a Signaler had suffered a direct hit by a German artillery shell on 19 April and had both been blown nearly completely apart. What little remained was buried on the spot—at the foot of the eastern slope of Mont Kemmel in Belgium.

It is typical of Hodgson to have volunteered for a dangerous mission a week after leaving the hospital. The reward of bravery is often a painless death; it became his too.

Yet the bravery I personally appreciate most in Hodgson is not the physical one, but the spiritual, because that is so much rarer. What I refer to is that he had the courage to acknowledge the existence of what we now call cosmic horror: a radical and more than inhuman evil, which is present in many of his tales, sometimes breaching the protective barrier humans have been granted around our existence by divine grace, but can erode through our own actions. He was a major influence on H. P. Lovecraft (1890-1937) for this reason.

But unlike Lovecraft, Hodgson was simultaneously strong enough to believe in pure and lasting love. That is why I consider him so uncommonly brave. Because of the ability to see simultaneously the darkness and the light, and not fear either. It is the kind of strength that Joan Grant has described in the quotation below — a text not included in her novel Eyes of Horus (set in Ancient Egypt, and a highly recommended read), but referring to the main character, Ra-ab, from that book.

Horus speaks to Ra-ab of the distinction between two kinds of love: The love of Ra (the sun god, father and creator aspect of divinity), and the love of Horus (also a sun god, but in the aspect of son, king, protector and healer of mankind)1:

Ra-ab, had you forgotten that at the time you asked me when you would be ready to wear my amulet, I said to you, ‘When you can give the Love of Horus.’

And when you asked me how that differed from the Love of Ra, I told you,

In the Name of Ra, all that is of Ra in you, will see all that is of Ra in the other; so that even if you speak with a Zuma2 of the Caverns, in the Name of Ra you will recognise the small spark of love which is within him: and while that flame of love leaps down the ray that unites you in brotherhood you will not smell the corruption of Set3, nor see that in him which is not of Ra. Even if he stinketh like carrion on which no vulture will gorge, you can still love him without fear, for by that protection you can enter the Underworld and find therein only the children of Ra.

‘But if you would have my sight, you must smell with one nostril the clean wind blowing through the fields of the longstanding corn, and with the other the filth that crawls in the belly of a dead crocodile. With one ear you must hear the words of a friend, and with the other the hiss of the viper of Ahanu. With one eye you must see the hills of the morning, and with the other the swamps of the unclean. And the two lips of your mouth must savour the good of a man and the evil thereof.

‘Then from your mouth shall come forth the justice of an Assessor who can weigh a man’s heart: having seen him, heard him, smelt the odour of his spirit; and so can show him in words both the vision which he should keep in his heart in honour, and the corruption which with the Sword of Horus he must cut from his flesh.

‘No longer will you be able to say, “This man is of the darkness and the other of the light: the first is my enemy, and to the second I will cleave until death unites us.” For they who wear my amulet must see a man as he is, and still love him.

‘It is more difficult to love, with clear vision of the whole, than to love only in recognition of that part which belongeth with us until eternity.

‘And when you wear my amulet you must take all your sins in one hand, and all your triumphs in the other: and you must forsake the comfortable valleys of humiliation, and the clear peaks of attainment, and take the road of the hills, where only the man can walk unafraid who can see the mountains on his right hand and the valley on his left, and still have the courage to continue on his journey, in company with himself, and those others who follow the same road.”4

This kind of balance is not for the faint of heart. To aim for it is to become the kind of spiritual warrior who will never again be out of the state of war. The best he can hope for is a furlough.

In one of his last letters home, Hodgson wrote from Belgium of what he saw at the front as similar to the Night Land he had seen before in spirit, and described in the eponymous novel:

"What a scene of desolation, the heaved-up mud rimming ten thousand shell craters as far as the sight could reach, north and south and east and west. My God, what a desolation! And here and there, standing like mute, muddied rocks — somehow terrible in their significant grim bashed formlessness — an old concrete blockhouse, with the earth torn up around them in monstrous craters, and, in some cases, surged in great waves of earth against the sides of the blockhouses. The sun was pretty low as I came back, and far off across that Desolation, here and there they showed — just formless, squarish, cornerless masses erected by man against the Infernal Storm that sweeps for ever, night and day, day and night, across that most atrocious Plain of Destruction. My God! talk about a lost World — talk about the END of the World; talk about the "Night Land" — it is all here, not more than two hundred odd miles from where you sit infinitely remote. And the infinite, monstrous, dreadful pathos of the things one sees — the great shell-hole with over thirty crosses sticking up in it; some just up out of the water — and the dead below them, submerged. And near the centre there was one cross inscribed to "Adolphe Dehaut, tué Nov. 26th, 1917." And on the centre of the cross, lashed with a piece of cross-wire, was an empty bottle, upside down. ("Turn down an empty glass," I suppose.) If I live and come somehow out of this (and certainly, please God, I shall and hope to) what a book I shall write if my old "ability" with the pen has not forsaken me. Who, I wonder, was Adolphe Dehaut? Some day, if it please God, I'll see that at least one French soldier's name is not lost in the dreadful oblivion that, like the mud of this hideous world, falls on the dead (…)."5

His heart remained warm in compassion for the soldier lying dead under water like the corpses in Tolkien’s Mere of Dead Faces. (Tolkien had first seen them in Belgium too.)

Hodgson’s novel The Night Land is a difficult read, not least because of its archaic language; it is not recommended for a first acquaintance with his work. But it is characteristic of his attitude by containing both a love story outside space and time, signifying a hope beyond hope, side by side with a depiction of the darkest and bleakest future possible for humanity: colossal eldritch gods and bloodthirsty animal-human hybrids dominating the world after the sun has died. The last remnants of humanity are hiding away in their last stronghold, knowing that it is only a matter of time before the dark ones will swallow them too.

To contemplate that kind of vision — and he had others not less horrifying, as the Carnacki stories and the novel The House on the Borderland testify — and still be full of desire to fight, to live, and to love — to be so aptly named Hope — is rare indeed. It is a great loss that he died so young. Who knows what he might have gone on to write.

I have written this bio of him because I want to share an audio version of a short story of his which always seems to be missing in audio form, although many of his other works are available as audio books, in numerous versions. I suspect that this one is avoided because a Christian theme — the Darkness of the Cross — features so prominently.

So I wanted to remedy its absence. It is a chilling, weird tale about scientific pride. It also demonstrates the inferiority of the education system of our time compared to his — I mean, if you consider that Hodgson left school at 14, and yet has no trouble writing such complex and fluent sentences as the ones in this story (something that is becoming markedly rarer in the literature of the new millenium) — not to mention the ideas in it, and the spot-on (loving) parody of scientists in their element — he must have gotten that from somewhere. Admittedly, he is reported to have been always reading, so acquired a lot by his own initiative… but still, I think it is indicated that he received a good basic training from without.

Today, writers are recommended to write as short sentences as possible… Pfft. Not that Hodgson’s prose is perfect (after all my eulogy, I suppose I should humanize him a bit here at the end): He has a tendency to repeat certain words within one story like refrains… That should have been called out by an editor in my opinion — but otherwise, well done, Mr. Hodgson!

So, please enjoy this landlocked seaman’s weird tale of the tragic spiritual ambitions of a biochemist:

The print (etching on zinc) is by José Guadalupe Posada: "A group of men looking at a man's back with an image of the Crucifixion." Public domain, Wikimedia Commons.

The Baumoff Explosive has also been published under the title Eloi Eloi Lama Sabachthani… which prompts me to end this newsletter by playing to you Chris de Burgh’s The Last Time I cried, in memory of Hope. The music video is below, after the photo of the war memorial with Hodgson’s name on it. Remember this one thing, no matter what, even in the weirdest terrors of this life:

Hope.

Cordially, Maria Rustica.

The last time I cried by British-Irish singer-songwriter Chris de Burgh.

Origen would probably have interpreted these two figures as foreshadowings of the Christian Father and Son, but that is another story.

A Sumerian (enemy of the Egyptians).

The god of the Underworld - in Grant’s book, a diabolical spirit.

Quoted from Joan Grant: Speaking from the Heart, p. 94.

Another fantastic post. I had never heard of Mr. Hodgson or his writing. I will have to look him up.