…and why language springs from vulnerability.

I. Why are we naked?

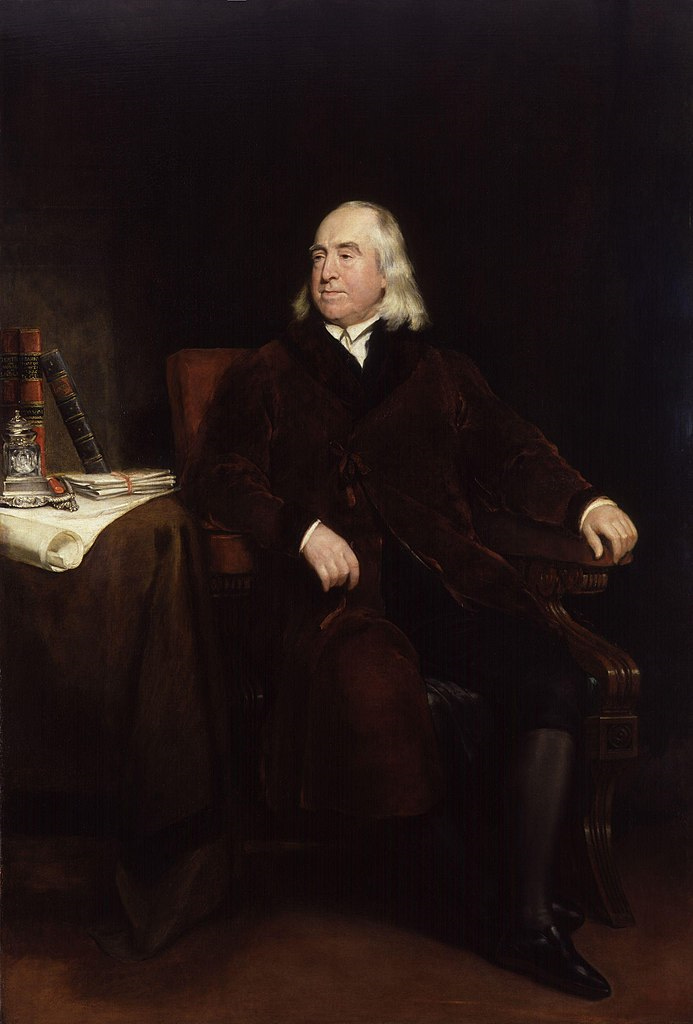

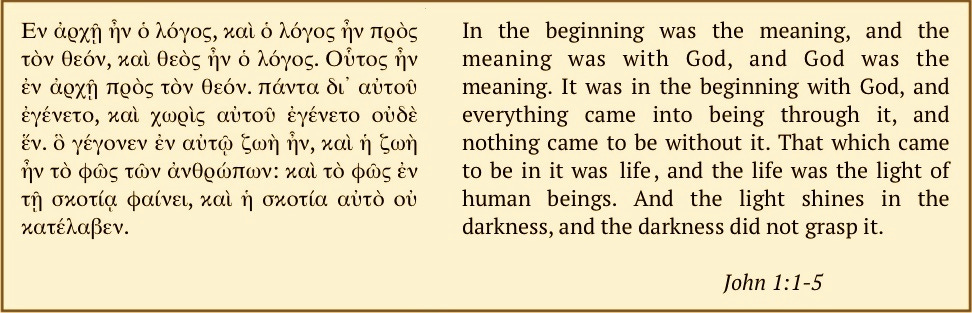

This image is from a painting created by the Bohemian-German artist Anton Robert Leinweber (1845-1921). What I like about it is that one of its many themes is communication: It says something important about the nature of communication.

First, that communication demands a minimum of two honest participants. You cannot (no matter how hard you try) communicate with someone who is not genuinely inclined to be receptive of what you have to say.

Second, that to be communicative in your intent is to be open and honest; whenever you speak the truth of something as you see it, you reveal yourself, and thus make yourself vulnerable to the other. It is a risk. You may, or may not, be received kindly. But if you are, you will be enriched by an honest and open response; this is like two open hands meeting and clasping:

A true encounter, a touch which passes on warmth, comfort, support − and insight; that makes reality more real to both. All who have experienced a true encounter with another person − the creation of a common space to move in − know that there is no greater happiness. To be a human being is fundamentally to be communicative.

Even our bodies tell us this; we are distinct from most other animals by being much more poorly protected in our skin, no shell, no scales, not even proper fur to cushion us; nor have we useful claws, fangs, or horns, to defend ourselves. We are exposed; and our children are helpless much longer than any other animal's little ones. But this exposure makes our skin better suited for touching and being touched: for encountering others and sensing more of them than we could through fur, feathers, or scales; and through that contact, learning more about ourselves and reality. We are all sensitive border (the skin is an organ, the largest we possess), and borders are where encounters take place… when the borders are respected, that is. The breaking of boundaries is another story, to which the painting by Leinweber alludes as well. I shall return to that shortly.

For now, the main point is that all this bare skin gives us a special opportunity for perception of one another, and for fine-tuning our mutual understanding. Which again broadens mightily the opportunities for cooperation. Language itself springs from such fine-tuned encounters − in other words, fundamentally from vulnerability.

Were we not so exposed to one another, and to hurt, nothing could matter to us as acutely as it does. But since we do hurt, and since it takes very little effort to pierce through human skin and cause pain to human nerves, we are compelled to great, and nuanced, attention to one another. I doubt that language could have arisen without this level of intense focus, enabled by our nakedness. Why are we naked? In order to communicate. For the sake of the encounter.

Every encounter takes place on a border, and the more border there is, the more intimately we can get to know each other. This is the beauty and the great hope in human existence. It is the potential for love.

II. Why words do trump weapons

Now, as regards the opposite: the breaking of borders. As it turns out, the opportunity for cooperation, though it grows from vulnerability, ends up bringing with it a capacity for its own opposite: the exercise of power over others. Our very vulnerability, which necessitates extra protection, disposes us to secure ourselves in a very focused way too. This can devolve into seeking power over others, and in the end, over everything on this earth: humans, other animals, plants, and dead matter. And our special gift − language, the forming of abstract ideas, which include physical and mental engineering, is eminently applicable here, too.

The strength of language − of the pen, or keyboard − is greater than any strength of fangs, claws or horns, or even than the ingenious war tools thought out by itself: the sword, and the nuclear bomb too. In the end, not only do all other weapons we produce depend on words to be thought out, and then constructed − but words, in addition, trump all other weapons in the end. If you succeed in persuading people to imprison themselves in their own minds, you hardly even need physical weapons to control them. No prison walls are as thick or impenetrable as those of a successfully sealed mind.

But words are not only the strongest of weapons, but also − which is far more important − the only possible resistance to the weaponization of everything… the only hope of dismantling power itself. If used to their full potential. Which is greater than anything else.

Words can do this. Because words are more than all is. Why are they more? Because power, ultimately, is reduced to destruction and the threat of it. While words create. Words can make the blind see, and open new spaces where there only appeared to be walls before. Words can heal the wounds of the soul.

It is a long time since humans caught on to this. The Ancient Hellenes, when they composed poetry, called it ποίησις (poiesis): making, creation.

A hellenized Hebrew wrote: Εν ἀρχῇ ἦν ὁ λόγος. ”In the beginning was the Word.” But it is no less true today. Power is only power, but words are creation.

In Leinweber's image, the two hands illustrate the difference. One is open, inviting to an encounter. Ready to both give and receive, openly displaying its own vulnerability. The other is in a different position. Unable to either give or receive anything, because it is clinging to a stone. The stone symbolizes power. The one who accepts such a stone into his hand immediately becomes bound by it, unable to touch any living thing as long as he still holds on to it. This expresses an actual principle of communication. To touch another person in a true encounter, you have to first relinquish all power. A person who seeks power cannot meet anybody in a genuine sense; he is, and remains, alone. Why this is so, will be further explained later; for the insatiably curious, I include a few hints here, in these selected clips from The Master and Margarita (2005 tv series by Vladimir Bortko):

So, what we see in Leinweber's image is two persons in close proximity, but any real encounter between them has failed. It failed because it is refused by one of them. The gestures of the hands show us this. One hand clenches its stone with a will and will not touch the other person or be touched. The other person's hand respects this choice and does not force a contact, but remains open, and even seems to perform a blessing.

But the blessing is refused as well, so love cannot flow between the two, it remains resting, waiting in the open hand in the form of compassion; and moreover, compassion at a potentially high price. For the stone-bearing hand is not merely a refusal, it is an armed hand. It demonstrates its power with the stone. It even pretends that power is an offer to be shared − presents the stone as if it were a gift. But power can only ever be held by one hand.

III: Why power and communication are opposites

So my point here is that the exercise of power and the act of communication in a very deep sense are opposites. If the person before you has made the choice to seek to exercise power over you − to force you into something, whether by threats, by violence, deceit, manipulation, or seduction (the five different ways pressure may be placed upon another will); whether by nudging or grooming or any of the other management methods we see so abundantly around us in this age, whether by carrot, or stick, or stealth − any method which tries to make you do something that you would not do out of your own free will if you were conscious of what was going on, and allowed to make the choice − then this blocks communication between you. Exercise of power in itself implies a breakdown of communication.

To the extent that a person pursues this goal − domination − he or she loses the ability to communicate with others. This is because actual communication is always between equals. I do not mean that the persons involved have to be equals in every respect of their existence. (For instance, parents and children cannot be equals in some ways.)

But what I mean is that true communication presupposes a willingness to recognize the other as an equal in the particular, and fundamental, sense that he or she is a different person from you, with their right to their own perspectives. Without that presupposition, you cannot even truly listen. I shall return later in the video to the (perhaps surprising) rôle of equality as an integral factor in communication.

I have chosen the image of these two hands as a constant reminder that we all, in every moment of our human existence, living with each other, have to make this choice: either to communicate openly and with an honest intention of understanding both the other person and our own goal truly (that is, without deception, including self-deception, which is easier said than done); or to opt for violence, for force. The exercise of power is basically violence in every case, whether by physical, spiritual, verbal or emotional means; for it is the attempt to make others do or say what they would not do or say out of their own heart, uncompelled.

To my eyes, the most beautiful thing in the world is a free animal.

Video by MTD Design, via Vecteezy.

That goes for humans as well as other animals. A living being picking its own way through life, under no pressure, no manipulation, no blows or chains, unfolding its very being like a flower, bearing its own soul like a fruit.

Among the many deceits of our age is the idea that freedom is the breaking down of borders. But that is merely violence. Freedom is rather to be allowed to keep the borders of your being intact, your skin whole and flexible, fully sensitive, so that it may feel to the fullest the warmth of a kind touch. So that it may enjoy the sun and the water and the friendly embrace of true loved ones. Also to be free to not be touched, except when inviting to it − to not be forced into proximity. The respect for borders, the reverence for human, bodily and spiritual, vulnerability, is crucial.

The condition of such freedom is once more communication. To be willing to hear and see when others set a border. To step back when necessary. It is an art to place yourself at the right distance to another person. This art is love. Love is, among other things, the choice to be in the right place. Not to force yourself where you are not wanted, and not to deprive others of the joy of your friendship when both you and they long for it. Love takes courage. The courage to show your own face, to be yourself among others, which is at once the greatest of all vulnerabilities, and the greatest strength we can gain.

We are all learning this art as we go through life. If we choose to strive for it, of course. We may also choose to train ourselves rather in the art of exercising power. Then, as we cannot move our hand freely anymore − because it must cling to the stone; meaning that a power monger must perforce halt the natural, ever-changing character of reality to remain in control of his surroundings − then we cannot grow further, either. We become desolate inside; and that is why the power monger lives in a desert, and one who would make the attempt of communicating with him, inviting him to change his ways, must walk out into the barren waste:

But is this not meaningless? To the extent that a person chooses power as his goal, there is no communicating with him. He will only play the rôle of a listener to learn more about you in order to use it against you; he will only show you an outstretched hand in order to grab you by the throat. So I ask, is it not meaningless to do what the open-handed person in the image has done: deliberately walked into the waste, a place devoid of food and water, suffering deprivation and loneliness he needed not have been reduced to, merely to reach out his hand to someone who prefers to clasp a stone? Why has he put himself there at all? I have said it already: Compassion is what you see in the gesture of his hand. He puts himself in the other's power to communicate his hope that the other in the future will begin to choose differently. He does not try to force it in any way; he just shows that the opportunity is there. By his presence he shows, at his own peril, that he harbours this hope, that he believes in the other's potential for rejoining fellowship, and he is willing to risk himself to pass on this message.

His outstretched hand is, I have said, lifted in a blessing. It is an acknowledgment of, and respect for, the other's unassailably free choice. It signals that he sees the other for what he is, and lets him be. Respects his rejection of contact, does not touch, but holds back waiting. This is an act of love: Love is often embodied as waiting.

So it is a beautiful story this image tells. It is also a dreadful one, for, as we know, the person in the picture paid a high price for bringing his message of compassion into the waste of the human heart:

He knows this, but walks into the waste anyway. Why? − And what does he do while he is there? Keep watching the hands.

IV. Four hands spanning existence

Let us look at his other hand, the one not reaching out to the other person; it is gesturing skywards, indicating that there is an alternative to power − that there are other laws than the ones established by brute force. Gentler laws that lead to a freedom like that of the birds who can travel on their wings where there are no roads and no seeming support to their bodies of flesh and bone. It is like a miracle, but observably possible. For os too, says this gesture. As the German poet Emanuel Geibel wrote:

"Do not forget that you have wings."

The other person, with his left hand, the one not clasping the stone, gestures downwards, indicating the hard rock, the laws of a nature characterized by determinism and death, necessity, fatality; eat or be eaten, there is no alternative, you fight the rest or you die by them.

What is the truth about life? Is it the one, or the other, or is it both, according to your own choice? The gestures of these four hands seem to span the entire existential challenge of a human life. What are your beliefs about the nature of reality, of your own life and your eventual death? How do you choose to act towards others on the basis of that belief? Will your pursuit in life be of power or compassion? Fight or fellowship?

It is not a choice lightly made, or easily paid for. As we have just seen in the clip from Jesus Christ Superstar, the choice actually begins with death. Keep watching the hands to see this. Remember, it is the very same hand that we see in Leinweber's picture, the hand stretched out in blessing, that we see here:

This can be the price of compassion. Because nothing enrages a devil more than compassion, since he mistakes it for contempt. In his world, an act of mercy (desisting from killing someone) is only shown to humiliate a foe the more. A devil does not believe that anything is ever done for the sake of another.

V. Existence is about drawing the lines of yourself

I should here clarify that my current commentary on these pictures is meant not solely as a meditation on the passion of Christ − but as a mirror of human existence in general. You do not have to be a Christian to be inspired by it, for the situation it depicts happens to every one of us in each single moment of our lives. Whenever we are in the company of another living being, whether human, animal, or plant, we must make one and the same choice: whether to approach it with compassion or to wield power over it.

Each choice reshapes our own being a little, so that we are in the course of our lifetime, line by line, drawing our own portrait. We may come to resemble either of the two characters in Leinweber's painting according to the choices we make. Often we only realize after an individual choice is made − sometimes years later − what it turned us into.

In Ancient times, ethics was mainly understood through this perspective: How your actions shaped your character. Built it or broke it. This only began to change on a broader scale as late as in the 18th century, when an Enlightenment-inspired shift of focus was made in ethical thinking: away from what we now call virtue ethics, and towards, at first, universal principles − ethics conceived as a duty not to yourself as a whole human being, not to the spirit of life, but to non-situational, and thus non-human rules. This view on ethics is called deontology, from the Greek word for duty, δέον (déon).

A little bit later, in the 19th century, yet another alternative approach to ethics was conceived, which is today the most popular one in the Western world: the utilitarian view, where the goal of ethics is to maximize desired consequences - often happiness - for the greatest number of people. In other words: The end justifies the means.

How the deontological position affects the character of the person bowing to a principle, regardless of how it affects real human beings in unique situations which may not correspond very well to the circumstances the thinker who put the principle into words had in mind − or how utilitarianism molds the character of a person who, to realize his utopia, is ready to kill any number of children, as long as that number is smaller than the number of children who will benefit according to his calculations − is no longer in the field of consciousness.

Real human life and theoretical ethics have, in other words, become increasingly alienated from one another. Our perception of ourselves has changed so drastically that a person's image now is understood to be how he appears rather than what he is. It used to be different. Obviously in Judaism and Christianity, where it is stated that mankind is created in the image of God, the image is viewed as the human reality − our being itself is depictive, reflective.

But the Pagan Ancient philosophers, Plato, Aristotle and others, were also well aware that a person's actions reshape him or her, into either something more beautiful, or more hideous, than before, a step closer to the angel or the demon in us, and they rightly warned us against disfiguring our souls.

Nowadays, we may be unaware that we can even do this. We may not perceive the image that is our reality at all, only the figure that we cut in a material or social mirror, which is ultimately illusory, fleeting and unimportant. Oscar Wilde, who understood modernity so well, warned against this mistake in his novella The Picture of Dorian Gray. The warning is: Be aware that there is an image somewhere that is your reality − your real form.

What is it? Have you any idea − at all? It can be rather difficult to see oneself − not only because it is frightening, but because it demands great discernment to perceive the image that is reality among all the illusions.

Clip from Wolfgang Petersen’s The Neverending Story (1984).

It is like the test in the 2008 movie based upon Otfried Preußlers version of the Sorbian fairy tale Krabat where (spoiler warning) the heroine has to point out which of the twelve ravens she sees before her is Krabat, the man she loves, in an enchanted form. How does she discern it? She hears that one raven's heart beats louder than the others'. Because he loves her, and is afraid for her. He knows that the evil sorcerer will kill her if she picks the wrong raven. But she manages to get it right: by choosing the raven who cares. Only our vulnerability is capable of exposing the truth to us.

We do live in an age of illusion these days, and the illusionary patch, the loss of reality, is spreading day by day like the Nothing in Michael Ende's Neverending Story, trying to lure people into a virtuality where they can pretend to have any form, just like demonic beings have always done... hiding behind so many masks, pretending that life is a video game: Even if your day-to-day job is to guide drones in a war to kill real living beings, and pollute nature − you may forget that this is the reality which remains, and forever, in the midst of the temporary illusions... the maiming, the suffering, and the irrevocable death are real. The blood cries out from the ground…

…and if you pour your communicative energy into the empty void of a chatbot, if you engage with the word-husks of AI, you forget that this, too, changes you, who are real, into something progressively more robotic, programmable, controllable. Virtuality is a road to impaired movement. An arthritis of the soul.

We have looked at the hand that reached out even to the claw of a devil in the hope that it might one day again become an angel by making a new choice, reconnecting with compassion, daring to become vulnerable like a human being. What shall we say to the sight of a human hand reaching out in hope to a robotic claw?

There is no communication potential in AI. Why? Because it cannot reach out to you in vulnerability; because it cannot suffer and die. Nothing is dangerous to it, nothing is a consequence, and therefore, nothing is real. It does not have in it the image that is reality, only the image that is illusion. It is the Nothing, consuming and defiling the real ideas organically born of spirit. Nobody is behind the mask. (Except, of course, for the mind of the programmer − the social engineer to whom the robot is but a tool to make you into another tool.) What is important to understand about reality is that it is something wholly dependent on the element of a true risk. To become fully real, you must become mortal. You must, in a spiritual sense, choose death.

VI. All communication begins with death

The story of the Incarnation makes that point: Even God cannot love his created beings fully without making himself vulnerable to them, and to death. All communication begins with death. Obviously, not with the event of death, or no one would remain to say anything. No, but with the real possibility of death. The exposure to it:

Once more we have seen the clash between compassion and power. How dangerous it is to venture into the waste, and to speak with the power monger. Only a trained warrior should even attempt it. One who knows how much he he has to lose. For as Tolkien warns in The Fellowship of the Ring, all blades that strike this enemy must break.

So it is not usually advisable to attempt any form of engagement with a power monger. They are better avoided entirely, when you can. But you still have to choose between power and compassion within yourself. That is why everyone needs to know something about how to handle such a confrontation.

Let us go back to looking at the hands again. Keep watching the hands if you want to know what is going on.

So, contemplating his own death, what is Jesus' response?

He folds his hands. What does this gesture actually mean, and why is it used in prayer?

Prayer is communication; on the one hand, you reach inside yourself when you pray, meditating on what it is you need or wish to ask or share, finding your inner truth to express it on the deepest level you can reach of yourself. So in prayer, you hold your own hands to be in touch with yourself (your real self). You need to get to know yourself better in order to pray truly. So you reach inside − that is one of the two things the clasped hands mean. The other, of course, is that prayer is reaching out to God. Communicating with God. But as God is not usually there in the same material sense another human being is, people will hold his hand in this way - through their own hand, so to speak. Prayer, in other words, is holding hands with God.

So, Jesus' response to imminent death is again: to communicate. He does not command hosts of angels to save him from the pain, though he fears and abhors it. He would rather pay the price of vulnerability than live in the loneliness of the waste that the use of power inevitably creates around a person.

So communication demands first and foremost courage. A courage unto death.

Every time you make the effort to be truly honest − to "put yourself out there", as they say − you will probably feel at least a whiff of that fear of death, you will feel exposed to death, and an imminent one. It is a necessary psychological process which is an important component in the practice of honesty. The death in question is not least an ego death, because honesty rarely makes you look good in the eyes of others. More often, it may make you look ridiculous or downright foolish, self-sabotaging or reckless - even at times unkind, though the gift of honesty is infinitely more compassionate than that degradation of self and other which a lie is.

In the words of A. H. Almaas:

Compassion is a kind of healing agent that helps us tolerate the hurt of seeing the truth. (...) Much of the time, the truth is painful or scary. Compassion makes it possible to tolerate that hurt and fear. It helps us persist in our search for truth. Truth will ultimately dissolve the hurt, but this is a by-product and not the major purpose of compassion. In fact, it is only when compassion is present that people allow themselves to see the truth. Where there is no compassion, there is no trust. If someone is compassionate toward you, you trust him enough to allow yourself to be vulnerable, to see the truth rather than reject it. The compassion doesn’t alleviate the pain; it makes the pain meaningful, makes it part of the truth, makes it tolerable.

(A. H. Almaas, Diamond Heart Book One.)

In another book, he writes of compassion that:

It eliminates suffering in a more ultimate and fundamental sense, by allowing the ability to see the deeper causes of suffering. Also, the increased tolerance and acceptance of experience allows one to just be, instead of trying to manipulate. This allows both objective understanding and personal presence. To be who one is is a compassionate act. It is compassionate towards oneself and towards all others.

(A. H. Almaas, The Peart Beyond Price.)

VII. A fool in truth

They say that only a fool speaks the truth. Because the truth is an abyss before

the feet.

A human being can never know it fully, only plunge into it in the hope that though it seems like it will crush him at the very bottom of the world, perhaps it is nonetheless, miraculously, a passage to reality − to real life.

Clip from Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989). - It is worth noting that Indy only obtains the courage to brave the abyss when his focus shifts from fear for himself to compassion for another’s (his father’s) suffering.

Reaching out for truth is always a leap in the dark. Which is one reason why Socrates called the activity of the philosopher a preparation for death. The truth is not something you have. It is something you throw yourself into, to participate in it according to capacity. The truth is the wilderness − that which grows uncontrollably. The truth is the forest of the errant knight.

Something lives in there, no one knows what until they go and see for themselves. And we do not all find the same thing on our journeys. Never will... Reality is a vast landscape. You choose your road through it. And be forewarned that death will always stand in the path of truth.

On the stone is written: To take the straight road is to not survive. There is no path. Neither for the one who walks, the one who rides, or the one who flies.

This is the voice of power warning you. To proceed any further, courage is the requisite: Courage unto death.

You can make it a little easier for yourself if you consciously watch this process happening as you communicate. Not only with others, but when you look honestly into yourself too. Consciousness of the mechanics of communication helps to be more at peace about it. With practice, you can get used to anything, including death.

VIII. Keep watching the hands

I have two further comments on the clip I showed you above from the 1973 rock opera movie Jesus Christ Superstar, with Ted Neeley as Jesus.

The first comment concerns the use of images painted by artists, instead of a flashforward of live action footage, to relate the reality of Jesus' death. This can be seen as an hint at what I just claimed about human reality: that we in a profound way are images ourselves, and understand reality through images as well. This is a central theme in my thought: the question of what images are, and how an image can be a reality when it can also be the opposite of reality, namely an illusion, a mask, or a lie. Please allow me to quote an aphorism of my own that often pops up in my mind when observing life:

The deepest truth will be surrounded by illusions like a bright candle by dusty moths. They will try to extinguish it, but one by one, they will burn out in its flame. While still on the wing, however, they may cast a shadow into your eyes exactly in that moment when you are seeking to orient yourself by, and approach, the candlelight they circle; a shadow many times greater than their own stature; or they may even, if your face is close to the flame, dive bodily into your eye and blind you. For a while. In time, the light of truth will again become visible to you if you choose to keep looking for it.

So, yes, images can be shadows obscuring the truth, and they can block your way to it. But other images can lead you closer to it. And without images, you can go nowhere. Certainly not in any direction worth travelling. Imagination, you see, is the road map of the journeying mind.

The other comment I wish to make on the paintings shown in the Jesus Christ Superstar clip again concerns the hands. The people who made this movie have obviously put a lot of thought into the images they chose. The hands we see in the sequence are, apart from Jesus' own nailed hands, all doing the same thing.

Folding their hands in prayer. Meaning that the persons who stay by the cross − who brave death when others flee out of fear for their life − are those to whom the personal relationship with God − in other words, an attitude of communication − is the most important thing in their existence.

They then become as moons to his sun, shining back the light of his divine compassion upon himself, as reflected by a human heart. You see how the artist Aleksandr Ivánov has shown this double light in the painting of Mary Magdalene meeting the living Christ in the garden by the grave:

It is the darkest hour before the dawn around the two, and yet they stand in an inexplicable light. The light seems to come from the two persons. Not from Christ alone, for Mary's palms, held towards him, are darker than the back of her hands, which are turned towards her own face. So both she and he exude an equal light of love and joy. Fully realized communication is a miraculous activity that creates equality even where it was not to begin with. Even where it would be thought impossible to attain. The reflected light is kindled within the mirror itself: the moon begins to burn like another small sun, with eternal life. God and man become kin.

What we see in Ivánov's painting is this process happening − not yet completed. That is why Christ's body is both revealed and hidden (shrouded), and his hand both reaches out and prevents Mary Magdalene from coming quite close.

"Μή μου ἅπτου," he says to her: "Do not hold on to me, for I have not yet ascended to the Father. Go instead to my brothers and tell them I am ascending to my Father and your Father, to my God and your God."

Everyone must go through death alone, even God. Christ's pilgrimage through the kingdom of death to the living God still has its last steps before him. Yet Magdalene's love for Christ is so strong that even that distance does not seem wider to her that a few human steps between them. Her hands almost reach across the gulf of death itself. And her eyes see beyond it to the eternity of life in love. That is why she is called the apostle to the apostles. Because she could witness to them that she saw truth through death. It is perhaps the strangest situation imaginable. The change it brings to the relationship between humanity and divinity is so sweet.

There is a beautiful passage (a favourite of mine) in the Medieval epic poem Willehalm by Wolfram von Eschenbach, written approximately between 1210 and 1217 AD, and celebrating this new relationship (which is not for Magdalene only, but for all who choose it). The poem's opening words are these:

The beauty is, of course, best appreciated in the original. If interested, you can hear how the passage should sound with the medieval pronunciation, here:

This is what communication can do. It is an alchemy that turns the poisonous and crushing lead of strangers and enemies into the bright warm gold of friends and family. It makes brothers and sisters of us all.

The focus of Wolfram's text, apart from kinship, is God's compassion. This is what the praying man is asking for. It is what a human being learns from society with God. The divinest of all qualitites, the great healer of mankind's hurts.

Let us see what happens if we follow it all the way to its conclusion. At what do we arrive? Keep watching the hands. What is the alternative to power mongering? The alternative to attempting to control others? … The alternative is creation.

Creation as a whole is an exercise in equality. It establishes an equal relation, it confers freedom.

Why? Creation presupposes equality because in order to create something truly new, something other than yourself − something that does not remain a mere puppet of your own will − you have to bestow upon it the gift of free will, of independent growth. Borders of its own, individuality. A finished form: a separate image.

Note that an image is not a copy of the thing it depicts. It is an original perspective on reality. Communication, and, indeed, language itself, is all about drawing borders. Just like love. (One might say that communication is love in action.)

This truth is symbolized by Michelangelo in this painting, by making the body of God the same size or even a bit smaller than that of Adam, his creation. The hands reach out to one another in symmetry, not one above the other, but mirroring each other one to one. Adam is created in the image of God, that is, he is made to be a creator too. He is made with the same opportunity to choose an alternative to power: to choose communication.

When communing honestly with one another, seeing one another and ourselves as we are − different − and not attempting to change, influence or control what we see − no nudging, no grooming, no pressure, merely responding to what is, as one human to another on an equal footing − we create something new. Something that no one can create alone. Fellowship. Togetherness in our individualities. This is the unique creative potential of human beings. It is not about creating bodies out of nothing, for that has already been done − we exist as embodied images. What human beings create, when they receive the gift of their free will with joy, is expression.

This, in fact, means that words are the specific human component in creation, not God's. (Just like it is Adam who names the animals in Genesis.)

God is above and beyond language. (More on that shortly.) − To be human is to create art: images and stories. In that way, we trace each others' borders, depicting each other, and so learn from one another. We grow together side by side to branch out spiritually into new places that we could not have reached on our own.

We help each other understand because every created being is unique. This is not a theory − it is easily observable. Not even two snowflakes are the same. Not even identical twins are truly identical. It is a continuous and observable miracle that is also the vehicle of our most precious gift to one another: communication. The art of understanding another, and stepping aside so that there is room in the world for him or her too. For their perspectives on the vastness of reality. This is why Dostoyevsky wrote in a flash of perfect insight that

It is a mysterious-sounding claim, but it makes perfect sense when you know what lies behind it. Keep watching the hands…

It is all in the painting.

IX. How the sting of death is broken

These hands speak of the laws of existence. As I have laid out, the hand that points to the rocky ground claims: "The laws of nature are implacable. We are mortal. And to survive even for a while, we must fight to the death against others trying to do the same; we must eat each other. Communication makes no sense, only as a ruse, for the only realistic goal is to conquer to live another day. Death is reality; reality is death. The rest is silence."

The hand that points to the sky claims that "there is another law. One that breaks death. Not through power. Not against nature. But growing through it like a grain of wheat that decomposes in fertile soil to grow an entire new ear of wheat, holding a multitude of grains. Life becomes stronger by going through death. But how is the sting of death broken? Through compassion. There is no last word."

Some say that one day, we may even come to understand God himself... if we care to communicate earnestly with him. It is a strange situation. But it is the story told in the image by Leinweber; and in the various other images in this essay. It is a mystery that intrigues me incessantly, and I would like to share my joy and wonder at the great forest of reality with you. Together, if others walk along a similar path, we shall come to understand more than we can separately. As Vasily Severyanin, the storyteller in my Grail romance A True Jasmine (not yet available in English), has put it:

X. Some words on meaning and reality

It is an ongoing journey, and I am but a traveller on the way. So take nothing that you see or hear from me as the final word on any topic. All my words and images are intended as open-ended and open-handed − no matter how categorical they may sound. At least that is the ideal I strive for.

The assertive, aphoristic form I tend to cultivate is only chosen for the sake of clarity of thought, but the thought itself may always be challenged. I welcome that. My thoughts are only invitations to walk somewhere and see the view there with your own eyes... from your unique perspective which no one else in the universe, in all of history, has had or can ever have.

I don't know the truth. But I try to find my way closer to it every day. Because I love reality, and because I love to learn. I hope the things I say may inspire your joy in learning and in creating words and images of your own − that activity called poiesis by the Ancient Hellenes who understood the art of poetry as an act of pure creation as such − and they were right: Where human beings are concerned, that is how we make things more real to ourselves − and it is how we ourselves become more real. Stories are no less than our road to reality. They are not reality itself, but they are our stepping stones to it.

So take a walk with me. Drop your stones, if you are holding any, and step on them, they are more comfortable as a path to walk on than the hot and crumbling sand. Once you stop carrying them around with you, they actually help you to move forward faster. They become your road. The renunciation of power is the stepping stone to spiritual freedom.

The insights are all in the image.

The logos was the beginning of the only world we can ever know. Logos means not only word in Greek, but also a story, and meaning as such. When I first realized that, the opening to the Gospel of John made sense to me on a new level. Here is my translation of it:

I shall return to the wider implications of this in another article. For now, I restrict myself to summing up the theme of this essay in relation to it:

In the beginning was the meaning of it all. Seek it out. Seek to understand instead of to control. Seek to see the other in his or her unique identity, not as an opportunity for conquest and exploitation... not as a clay into which you will imprint your own, already extant image.

Imprinting is the opposite of creation. It is stunting reality, and that is destruction: because it requires the erasure of the unique image which the other person has already been given, in order to reproduce in its stead the form that you yourself have been given... Do not attempt to remake others in your image. Only an unwise being will pursue such a goal − punily attempting to be like God. Anyone who tries that is always reduced to exercising power, to violence. But only a deeply impoverished being will reduce himself to a power monger's belief in stones in a universe of stories.

Stones are but the medium of death, and there is nothing more transient, more temporary, than death. Stories are the medium of life, and like it, they last forever. Tell your own. Here is mine. Welcome to my world.

Cordially, Maria Rustica.

Thank you for the restack, Asia! Appreciated.