One thing I have noted repeatedly when studying people in the wild is how much a person's relation to God is at the fore, whether they believe in him or not. People take offence to God. I cannot count how many atheists I have spoken to who are furious with God for not existing. They attack the idea of God not as an idea, but as someone who has let them personally down. Someone who broke their heart.

Not that I mean to imply that this is the attitude of all atheists. Ultimately, there are as many attitudes to God, and to existence in general, as there are individuals. Some atheists are indeed calm about the question. Some don't mind existence. In some ways, we all possess a unique perspective on the world. But in other ways, there are patterns; and the one mentioned above, the fury with God, is one of them.

Such atheists cannot simply register that they do not believe in this idea, and let it go; they have to pursue it, some even set out to eradicate it from the world. Some wish the idea of God gone because they see it as a tool of control over others, a trick used by humans against other humans for mere personal gain.

No one can deny that this is a historical fact, both in the past and ongoing today; people are like that, unfortunately: They will use anything and everything as weapons against each other; and of course, they will be especially inclined to use the sharpest tools in the drawer, when they can get their hands on them. (Dragons appear where the treasures are.)

The idea of God is just about the sharpest tool there is. Atheists are right to see that and fear the consequences of others using such a weapon. But from an existential point of view, the interesting question is: Why is it the sharpest? — What is it about God's name that makes people long to die for it, even when it is used as a lie?

If atheists are right, God is a mere conceptual invention. A fiction, like emperor Palpatine in Star Wars. Something children should only be frightened with for fun around a camp fire, not for life to keep them under a yoke. But why would he frighten anyone for life, if he were a mere fiction? We fear physical death, and pain, because we experience them as fact. When people fear God's judgment so strongly that it can be used against them, what is it they fear? What kind of experience does the fear spring from?

I am not pushing this clammy question into your face to use it as an argument for God's existence, some sort of proof by engagement. No. I am dangling it before your face like a dead fish just to remind you that you probably know this uncomfortable feeling from somewhere in your past... the feeling that your existence is somehow unfair.

It can be a sense of deep indignation, resentment, or anger. It can be directed against God, for not existing — or for existing and allowing the evil you have suffered, and the evil you see happen to others all the time. Including to innocent children, to animals, to all that breathe — damage and death, pain beyond belief.

Finally, it can be directed against God for creating this world and putting you in it without your consent. "Why are there beings at all, and why not rather nothing? That is the question", roared Heidegger. This question can be asked not merely in wonder, but in accusation. It is not as uncommon as one might expect to hold the opinion that nothing would have been better. Or at least to entertain that possibility. “[I]t would be much better if, on the earth as little as on the moon, the sun were able to call forth the phenomena of life”, hissed Schopenhauer.

Because an existence not chosen can be viewed as a form of violation. Indeed, it is at odds with the nature of the will itself, if you pause to consider it.

I call it the paradox of the given will. The will is what gives us ability to choose and act on our own choice. Will, freedom, and dignity are intimately related. Choice is fundamental to personhood. (It is not the only thing that constitutes personhood, but that is another story. For now, the paradox of the given will is our theme.) The paradox is this: How can you say you truly have a will of your own if you did not make the most fundamental choice of all: whether to be or not to be?

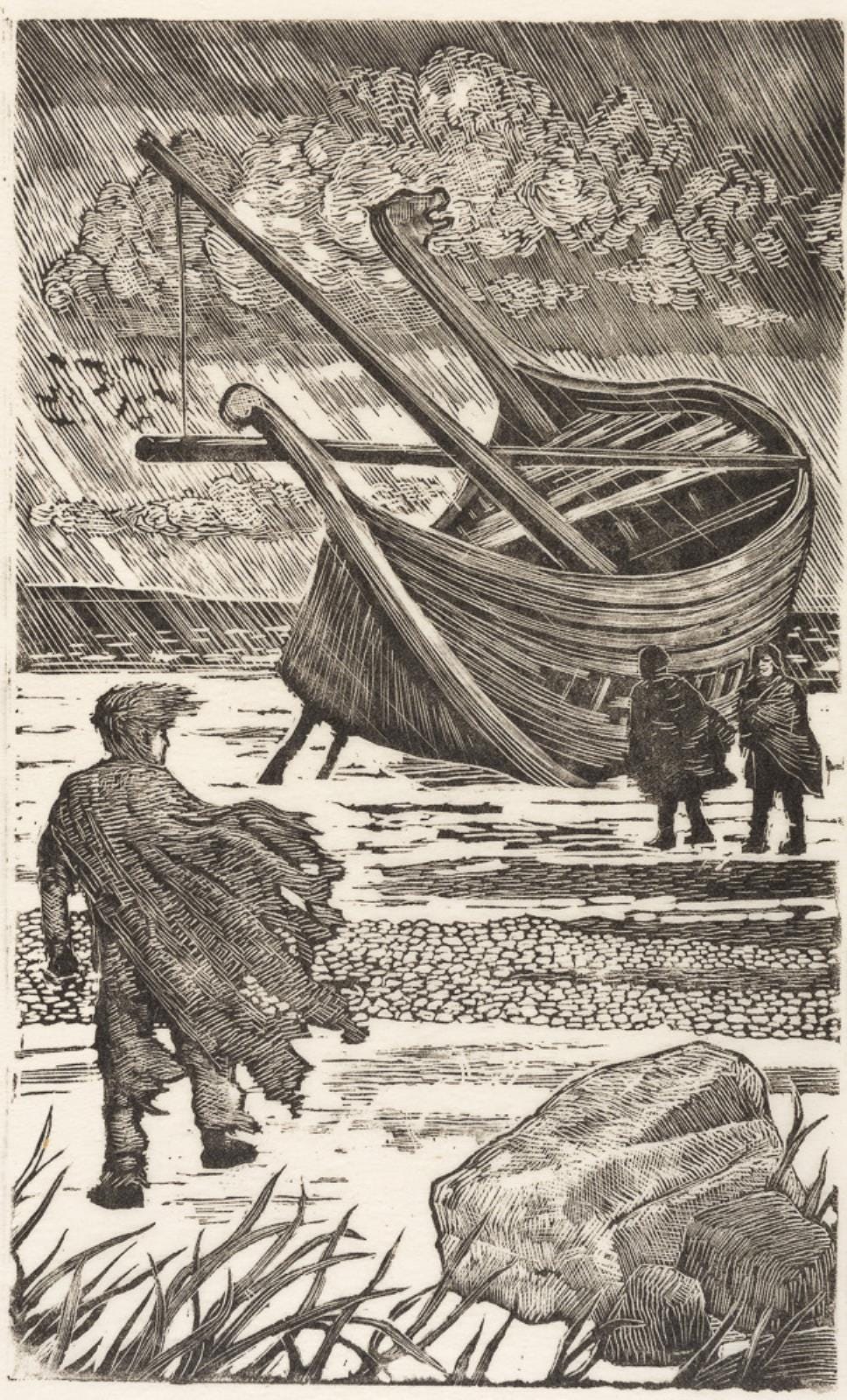

Shakespeare knew it. Hamlet's suffering is so deep because he senses the deeper symbolism lurking behind the literal traumatic events he has to respond to as best he can. The murder of his father, the usurpation of the throne, the incestuous uncle bedding his mother. Everything holy to his home, and to his country, defiled. His very origin is defiled. And he himself apparently both powerless to do anything to right the wrong — and demanded to do so, if he is ever to consider himself a man in a true sense.

There is no way (he decides) that he will go ahead and live life, start a family of his own, while this problem is staring him in the face. He is prepared to let his betrothed Ophelia lose her mind and life over this loss of a livable future rather than accept his fundamental existential condition as a fait accompli. He will not bow to the injustice, cost what it may. He will not accept life under such conditions.

Hamlet has his revenge, but the only way to attain it is to undo his own existence. To reject life. Hamlet and Ophelia both make this choice, each in their own way. Violence and death — insanity and death. They are the male and female ways, respectively, of rejecting the offered gift of existence. Destruction and self-destruction.

The enduring power of Shakespeare's play Hamlet to fascinate of course rests less on the literal story, exciting though it is, than on this deeper existential dimension. Hamlet is wrestling not only with the torment of his own seeming impotence to change the unbearable situation, nor only with the incongruence between honouring his mother and blaming her for complicity in his father's murder — the inner fight between filial obedience to his mother, demanding that he lives and let live, accepting the unacceptable — and filial obedience to the spirit of his wronged father, demanding revenge. Hamlet is certainly put in an unfair situation on the literal level...

But he also suffers through the fundamental unfairness of all human existence: that we did not create ourselves. That we may have been given the will and ability to choose — but we did not choose to be originally, so we have to make the choice to either accept what is — or not to accept it, and not be. To live with our human condition, or not to live at all.

But the horror does not even end there. The next horrible question is: If we decide against existence, can we even take back the gift entirely, or are we stuck with being? Is there an eternal life hidden behind the curtain, a gift that cannot be returned? Would that not be a true hell, even if designed to be a heaven, if you truly did not want it?

Adrian Lester: Hamlet’s soliloquy, Act III, scene I. To celebrate the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death in 2016, the Guardian had a number of “Shakespeare Solos” like this one made. I’ve never heard the rejection of existence spoken with such weary intensity.

The story of Lucifer's rebellion in Heaven can be read in this light. His original sin is said to be pride. Pride is a will that will not bend. In the present context, we may interpret that as a will that will not accept its nature as a created will, a gift. We can view the rebellion as an act of attempting to undo this (in his proud eyes) unbearable situation.

An attempt to conquer what was given, in order to make it fully your own.

But can you? Can you unravel your own given existence, deconstruct it, then recreate it on your own? Can you break the image of God within yourself and remake yourself in an image wholly self-chosen? If you shatter the original image in its entirety, what will then be left to make the choice about what to become afterwards? If you are a creature, can you ever escape your created condition?

Is it not a hopeless endeavour, leading to endless despair? To what Kierkegaard in The Sickness Unto Death describes as ˮan impotent self-consumption" (en afmægtig Selvfortærelse)? An existential state aptly illustrated by the figure of Ouroboros, the serpent (often drawn as a dragon) that vainly tries to swallow its own tail, thereby locking itself into a ring of perpetual imprisonment and hopeless fight against its own being.

If this is so — if it turns out to be impossible to undo yourself — it may be experienced by the resentful mind, by the will that despairs from not being fully its own, as the final humiliation: a Hell with no escape.

"Why did you make me? How could you do this to me? I was not given the choice: to be or not to be! You merely said: I am. And there you were.ˮ I am the one that am,ˮ you said: “אֶהְיֶה אֲשֶׁ אֶהְיֶה ,” you said, “’ehye ’ăšer ’ehye: I will become what I choose to, I create what I create, I will be because I will be.” — “ἐγώ εἰμι ὁ ὤν,” you said, “egō eimi o ōn: I am the being, the one in being” — “being by my own will, willing myself into being”. — You created yourself out of nothing! Well, good for you. Nothing impeded your will, so you conquered all of nothing! Well done.

But you did not let me do the same! You made me. You made me be. Everything is your fault!

Even my will is not fully my own, for I never decided whether I even wanted it or not. And I can never attain what you did — never reach omnipotence — not only because my will was given to me — without consent —, but in addition because you are here, in the same universe, another will to contend with, someone who can act upon me, do things to me against my will. And to make matters worse, you made not only me, but a multitude of wills. An endless amount of competition, a potential state of total and perpetual war!

How could you do this to us? Present us with a crippled will, a feeble will, a will that can only be partially satisfied, a will that can be — that always already has been — violated, by the fact of being given. How could you subject us to the humiliation that is existence? How could you make us into warriors, create us in the image of a cosmic warrior who fought and conquered Nothing – the dragon of non-existence? But we, if we are to ever be as free as you are, must conquer not merely that dragon, but you. God. You, who violated us by making us live."

You (the reader) have certainly seen this resentful attitude in art, particularly in the art (or rather, as it originally honestly called itself, anti-art) of the last century, setting out with a will to destroy all the images, all the meaning, that it could, and particularly the image of God. Of life, of being itself. You can certainly hear the strangled voice of Ouroboros, screaming through a mouthful of his own flesh, in Nietzsche's battle cry:

God is dead!

The torment of Hell is real; and within its own boundaries, it is perpetual. There is no solution to this paradox within the realm of the will itself.

(To be continued...)

I leave you for now with one of Edgar Allan Poe's visions of existence. But don't let it bother you too much: It is not the only thing there is to see.

The Conqueror Worm

Lo! ‘tis a gala night

Within the lonesome latter years!

An angel throng, bewinged, bedight

In veils, and drowned in tears,

Sit in a theatre, to see

A play of hopes and fears,

While the orchestra breathes fitfully

The music of the spheres.

Mimes, in the form of God on high,

Mutter and mumble low,

And hither and thither fly—

Mere puppets they, who come and go

At bidding of vast formless things

That shift the scenery to and fro,

Flapping from out their Condor wings

Invisible Woe!

That motley drama — oh, be sure

It shall not be forgot!

With its Phantom chased for evermore,

By a crowd that seize it not,

Through a circle that ever returneth in

To the self-same spot,

And much of Madness, and more of Sin,

And Horror the soul of the plot.

But see, amid the mimic rout

A crawling shape intrude!

A blood-red thing that writhes from out

The scenic solitude!

It writhes!—it writhes!—with mortal pangs

The mimes become its food,

And the angels sob at vermin fangs

In human gore imbued.

Out—out are the lights—out all!

And, over each quivering form,

The curtain, a funeral pall,

Comes down with the rush of a storm,

And the angels, all pallid and wan,

Uprising, unveiling, affirm

That the play is the tragedy, “Man,”

And its hero the Conqueror Worm.

(Edgar Allan Poe 1843)

It is hard to put into words how much I enjoyed this post. I have noticed the same response from the atheists I have encountered. It is more accurate to call them misotheists because the idea that anyone has faith in God to them is an affront. I find the rest of your argument to be completely on point and am excited to read the next part. I appreciated the closing poem from Poe. Well done!