(A Good Friday short story on God’s love for the lost, and one woman’s love for God.)

Hers was a grace which infused all, both internal and external. Externally, she was starry eyes and sunny smile; internally, beautiful from a joy that lived as the foundational layer of her life, as a subterranean stream carrying away all that was uncouth from her soul; and no evil that might befall her could change its direction or quench it. Thus she was who she was, and a special love for her was kindled in God.

It made him humble inside as he had never been before, for he wanted to step forth before her eyes and ask for her faith; but understood that he could only do this as any other wooer. He would have to reveal himself as he was, and could only hope. That he was God no longer made any difference. Exactly this made him hopeful as never before, allowed him to hope for something he would never have dared to hope if it had not happened to him in this way. But was it possible?

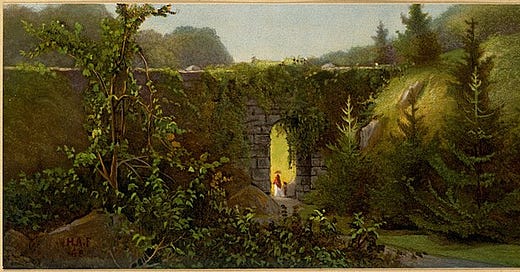

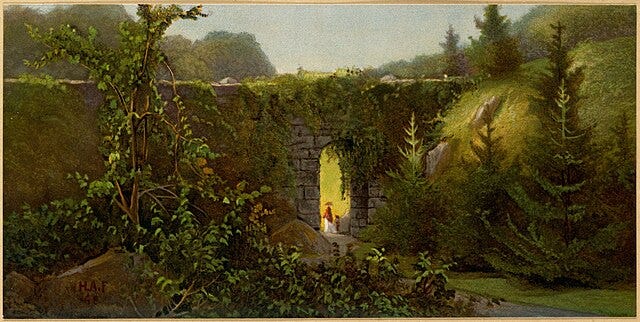

One day, as she was standing alone by the river, he came walking by the water's edge among the rushes. He looked like a man, and it was not a lie, although it was not the whole truth; for this was how his feeling for her made him appear. His being in love gave him this shape, for with God it is so that everything about him takes shape from what it really is. God cannot lie, only be, and that is why he has been hiding for so many years... for there is nothing people have to get used to so warily, and so gradually, as reality. God hides himself because he does not want to frighten anyone. And when he does appear, he only shows as much as each can bear to see. This woman's beauty and inner stream of joy called him forth in the shape of the handsomest of men: as one of her own people he appeared, but there was a light about and in him. He greeted her, said who he was and offered his love. And she saw that God was trembling.

Her strength in joy was the greatest human capability. It was great enough to see God for what he was. And she understood that he was lonely. She saw that the man who appeared to stand before her was but an image of a god who had not yet become man, that his form was the longing to become so. And she pitied him infinitely, and she did not fear him.

She said something to him that was beyond his wildest hope.

She said: "I receive you, and I will not only love you, but I will bear you within me and give birth to you. You shall never be alone any more for all eternity, for I am with you."

She opened her arms to him, and he walked into them and stayed there as a light and a sun now suspended, shining, above her inner waters.

When he was born, he was the handsomest child you could imagine. He was so happy because he had been received as what he was, though he was the most unusual of all. And the happiness showed as beauty.

As he grew up among humans, and enjoyed it so much himself, it touched his heart in a new way that not everyone had been so well received as he had. That dreadfully many were not loved at all. He pitied all of them, for no one knew better than he what it means to be alone. Was that not why they had all been created? So that there should be no more loneliness... so why did they walk about lonely in their own midst, and made each other lonelier still? Oh yes, he had seen it before, but he had not understood it, and now he understood it less than ever, now that he had experienced what humans have to give. He wished with all his heart to pass on what his mother had given to him.

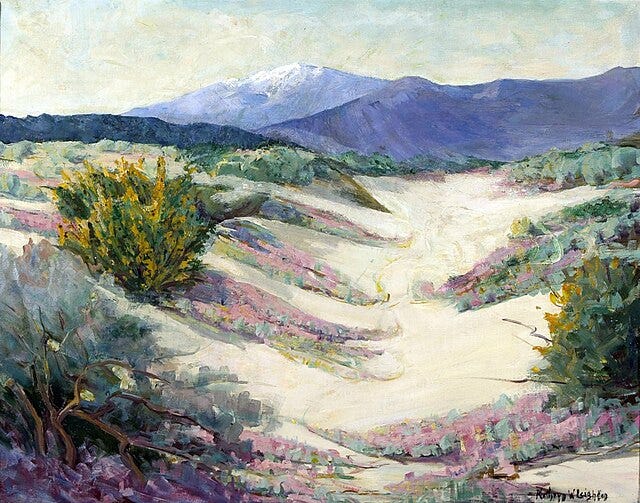

To better understand people's loneliness amongst each other, he walked out into the desert to perceive it from a greater distance. But as he placed himself in this position, and stood there gazing far and wide as one who is alone, the one came to him who had once abandoned him and refused to have anything to do with him — so long ago, even before there were humans. When God saw him again, he realized that this loss was part of the reason why he had been so afraid when he offered himself to the one who had now become his mother. He had once been abandoned because of what he was. Abandoned without having done anything, except being who he was. Now he saw that the one who had abandoned him had become quite dark, like a shadow, to look at — like the shadow he himself cast on the desert sands, now that he had become human. But the other cast no shadow, for he was not standing in any light. About him there was nothing human. But why had he come?

The seeking God now recalled that he had seen the same one many times come to those who were alone and isolated. He always did; only now did God begin to realize what it was about. And now, as the Other saw that the one he had abandoned had become human and was placed in the situation of a human being, he approached him with what he was capable of with regard to humans — what he had found when he had wandered away from God into the waste, and become alone himself: power. And his teeth protruded from his mouth as he was saying: "Now you are weak and empty, for here you must suffer hunger."

For he had seen so many humans be alone around each other; alone, though they had lain in a belly, and hungry, though they had fed near a heart. For so many hearts were cold and empty, and there was no nourishment for the children's souls.

The other showed God the power which lay as a stone in his hand, and he said that this was nourishment for the hungry. It was replacement, it was wealth; he reminded God how many humans long ago had learned to understand that stones are precious; he showed God his treasure, the one he had gathered himself. But the happiness from God's overflowing heart streamed from the radiant gaze of the young man, and the Other could not lift his graphite eyes to meet it.

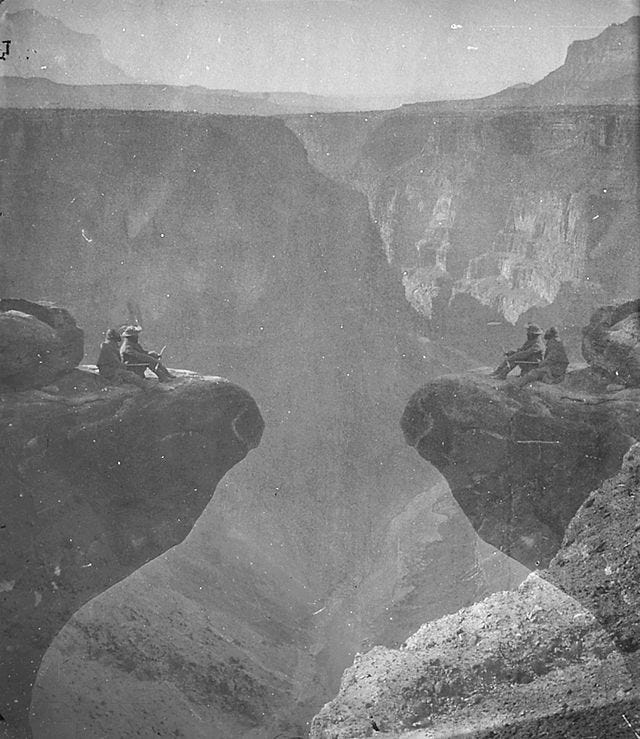

In the first instant, God had hoped that the outstretched hand with the stone meant a gift, and that the Other would like to be with him again. But from his speech, he understood that the Other wanted to tell the one he had abandoned about something he possessed himself; and as God could see nothing at all arresting about these stones, he could not think of an answer, for he did not wish to push the Other away. Therefore, he merely looked at him with the gaze that the Other remembered as what he had gone away to relieve himself of, and now felt that something more had been added to, which made a pointed horror prick his footsoles, like tiny needles sprouting from the ground beneath him. The Other kept his gaze down, so that the horror should not reach further into him, and took a few steps away to change his position from where he was stung. God carefully followed him, and they came to a high rock.

The other pointed into the abyss, in the hope that God would see his human face mirrored in the deep, alone in the great desert; for he himself was, if possible, even darker than before here in the heights — just an extra shadow, and he whispered, in order to make it sound more like an echo, and almost become a thought inside the young man himself: “You are not who you are now now: A human being who walks over this edge will suffer. Only a God who stays beyond anything human can fly as you are used to. Humans fall. Therefore, humans are thralls. Only a God is free; only a God is himself."

But God looked into the dizziness of the deep and remembered the safest thing he had ever experienced: to lie in his mother's arms and feel how gently she took care of him at all times, so that he did not bump into anything. By becoming fragile he had received so many opportunities to experience her love which one who was invulnerable could never have. As a human being he had enjoyed to entrust himself into the hands of another. Then he directed his gaze anew towards the one who neither was God, nor had ever become human — but this time with an infinite compassion that seemed to replenish the entire desert, like grass ready to sprout forth under the sand everywhere — for he said to himself: 'Yet there is one who is even more alone than I was.'

Yet here was a distance he had never known — he, who knew everything else in the cosmos because he had created everything else. But here was something he had not created. Here was what the Other had truly succeeded in bringing forth on his own, as his own. Again the Other could not look into God's gaze. He suffered by being so near to God; it stung and burnt him. But he endured it, because this situation was his great chance, that was how he saw it. So he remained standing there, even though something that looked like black blood flowed from the corners of his eyes. And now, for the first time, God asked him something. He risked making a request to him, for he sensed that here was the answer to both what he had come out here to seek, and what he needed to understand to even be able to dream of one day obtaining a reconciliation with the one who had abandoned him.

He asked of him: “Show me your world.”

And the Other, who by the second gaze almost had fled in spite of all his will to stay, and to power, here felt a small, new hope of obtaining what he wanted from this desert and from this human being. He lifted his shadowy arm, and instead of pointing into the deep, he pointed away from the high cliff to a vista of all the Earth, which to the infinitely sharp eyes of the two was brimful of people, cities, and many kinds of stone.

“All this can be yours,” he said: “When you had created it, you felt left out, and then you came to the flesh. But it has only led you here, into the desert. I am showing you the way out: Instead of creator, you can become ruler. Then they will all be yours. I can teach you what to do — teach you the language of stones and the deep…”

He spoke eagerly, and God felt a little sting in his heart by seeing in his eyes a reflection, a flicker, reminding him of what the Other had been like when he was still with him, and they spoke together of living things.

“You do not have to settle for one woman," said the one who had abandoned God; but then, God exclaimed: "Settle?" and laughed into the deep and the world, so that the stones fell from the hands of the Other, rolling down the slope... laughed from out of the stream of his heart that flowed so great and broad and singing that he could not hold it back. His entire happiness was clear to him in that moment. He was the beloved God, and he could not hide it the least bit from himself or the world any more. It broke out from him, it shone through him, and the Other did not endure it; he turned from him and fled.

As the grown man returned with his free gaze in his golden face, he changed all who saw him. He was an abundance flowing through the city's streets, and he began to teach what he himself had learned from and with his mother. He healed the sick. For he understood one thing: that loneliness was the misery of the world, and that it was the enemy of all, and his only enemy. It touched him deeper than ever, now that he himself had been freed from it, and now that he had seen how the one who had once abandoned the communion-seeking God had himself become lonelier still, and today was roaming the Earth for other lonely people, trying to draw them to him with the only thing a lonely person has (or the only thing he believes he has): this power. These stones that he placed in their chests instead of hearts.

But God's beauty and joy awoke the hearts of many, so that for the first time, they sensed that they had them, and what they were, and how to pass the life in them on. And his mother loved her son and was so happy that she had brought into the world the greatest beauty of all, and watched it grow day by day.

But after he had returned from the desert with the insight that he had set out to find, God lived on with a little longing inside him. He knew that no one would understand it, but he could not help thinking about it. He dreamed about it, and therefore he told people around him a tale of a lost son who returned home. He described in detail the feast he would then prepare. But people did not like to sense a longing in him. He had himself awoken one in them, even in those closest to him — in everybody except for his mother, who was the only one capable of receiving him fully, and therefore lacked for nothing — and it was a longing for more attention, more love, for being fully relieved from loneliness.

None of the others could be fully relieved, though receiving great joy from being with him, because none of them was able to accept God fully as he was, or themselves fully as they were. That is why they would sometimes fight over who was to sit next to him, and each of them would try to obtain the most of his attention; and that was why they did not like the story of the lost one, for this was where they got the strongest feeling that God's attention was elsewhere too, not only on them. Here they sensed that something was touching his heart particularly deeply; and when he tried to hint who the story was about, they became really angry; for they feared the Other and did not like him. This saddened God, for in this too there was a great loneliness. He inserted the others into his story, partly to give them the attention they wanted, and partly to warn them against this; and then he ceased to tell it anymore. But he still dreamed.

One day in his joy, his beauty grew so great that those whose hearts were stone could endure it no longer. For their master had not quite left the world, but had in burning rage ruminated for three years and concocted a new plan: a revenge for the infinitely compassionate gaze in the desert, and for the laughter from happiness that he had heard and not been able to share.

‘He is a human being,’ he said to himself, ‘and human beings can not only be won over by power, but also be destroyed by power. If he is not willing to leave his humanity behind, then I shall take it from him, and take him from his mother, whom he loves, and who loves him.’

He also knew that human beings can be not merely removed from the world, but also tormented, and he inserted into those whose hearts of stone were gnawing them, and whose inner empty spaces were echoing hollowly at the words and smiles of God, and who hated his healing hands, thoughts about how they could get get rid of him.

It would probably have happened anyway; the sight of a happy God was too much for many. It made all the things that could be changed turn so visible. But no — it was simpler still: His abundance was simply too great. So they took him and broke his body.

When he had suffered much, the Other returned to him. He stood in the corner of the prison and watched how these people beat God.

When they had gone away to sleep, and had told him: “Tomorrow, you shall die,” they remained alone together, the son of man and the inhuman; God and the one who had abandoned him.

The Other looked at God with all that he could muster of gaze. He knew that a new loneliness had now begun for the one who had become human, and that from now on it would keep growing until it killed. It was a loneliness that he had not known himself, for only a creature of flesh can know it: the loneliness of being tormented. It is not equal to that lonely way you can be together which is known by most people in this world: to live side by side and yet remain strangers. This other loneliness is a way of being together that annihilates one of the participants. And God suffered by it. He understood that the one who is annihilated is the one who believes he is annihilating the other. And he lowered his gaze.

Then the Other spread his wings so that they spanned from wall to wall. For he did not understand what God understood: that in this moment, it was not only God who experienced a new kind of loneliness — but that all loneliness in this moment reached its utmost limit and became fully concentrated into that most terrifying of all lonelinesses: the loneliness of the tormentor, which now became wholly real as in a moment of creation. There was one who was about to torment God to death, and who knew it. With the others, it was different: They did not know what they were doing; but the Other did. If he had looked into God's gaze now, he would in it have read the full meaning of his own deed, and he would have disintegrated. God would have destroyed him, whether he would or not, through his own reality, just by being what he was in this exact situation.

From then on, God concentrated only on one thing: keeping his gaze down. To protect the one who triumphed from annihilation. And he himself did not know if he could. For if his gaze should fall upon the Other, his will would not be able to prevent the annihilation. And his gaze passed through human eyes, and the human body is frail. It now depended, not on God, but on a human being, whether the lost son was to be irretrievably doomed. God closed his eyes, and thought with all his might of his mother. He saw her face before him, in the moment when she said to him: “Come to me: I will give birth to you, and you shall never be alone again.”

His heart called upon her to be with him, although he could not see her. For he was locked inside a human being, and this human being was in prison. Then her image lit up in his heart.

“You shall lose your humanity again,” said the Other, “and the one who gave birth to you shall see you die. I shall take you from her, and humanity from you. Now they shall become more alone than they have ever been. For they shall experience that God dies from them. And after that, they shall be alone with me. For to be alone is to be with me. Mine they will become, and you too will become more alone than you were.”

In God's closed eyes, the reflection of the Other's own loneliness was hidden, the only one that he himself did not mention, and the one that he must not come to know — only hidden from him by a thin layer of human skin and the will of God. Never has a greater distance existed in the universe than the one between the two in that moment. God's love for his mother, and his longing for his lost son, brimmed over in him, like the blood that was dripping into the dust, and he lay down in it at the other’s feet, and prepared to endure unto death.

The next day, when all around him were screaming for his death, he concentrated only on the one thing: keeping his gaze down. Because he had dedicated everything to that, on the threshold of death it came to be that this made him completely human. Now he did not merely understand what it is to be human: His choice had also turned him human in a way that only endurance unto death could do. The death that he was now to go through for the first time.

In that moment there was no God anymore. He had undone himself in order not to undo his own creature; he had sacrificed himself.

“Now you are alone,” said the Other who was standing at the foot of the beam he was nailed to, and watched him die: “You are alone, for I am with you.”

Now that he was no longer God, the tormented man dared to turn his face towards his mother; and he asked his best friend, who was standing by her, to take care of her, so that she should never be alone in the world. He prayed for his mother, and they looked upon one another for one last moment. As he was no longer God, she did not see in his gaze what the Other would have seen. She saw only that he had sacrificed himself, and she kept it in her heart.

Then he lost his vision, because death came quite close to him; and in that moment he was so entirely human, that he no longer even knew he had been God. He then called out to the God that he had sacrificed, and now forgotten — and simultaneously to his son, whom he had never before dared to ask this question directly: “Why did you abandon me?”

And he died the blind death of a human being. And the one he had blinded himself for saw it happen, and laughed.

Epilogue

In the beginning were the waters. The waters that stream longer than tears, richer than joy. At the foot of the cross, the mother's soul brimmed over. When the man on the beams was dead, God existed only in his mother's heart. Here he lay for a while and hid himself, as he had lain in her belly, hid his face and his mind from the world; and the world outside was dark as one vast womb and one vast grave. From that heart he flew at first again as a white bird; from it he was reborn, saved from annihilation only because he had been loved as he himself had loved.